|

| Andy McShea, front with fellow Whim W'Him dancers in Dolly Sfeir's hard times for dreamers. photo @ Jim Coleman, courtesy Whim W'Him |

One of the pandemic’s upsides (you read that correctly, there were a few) has

been the opportunity to see artists with new eyes. Or at least, eyes that have

had a protracted break from live performance.

Last weekend I was happy to be in the Erickson Theater audience for the opening night performance of Seattle contemporary dance company Whim W’Him’s 13th artistic season.

I’ve followed artistic director Olivier Wevers and his dancers since their first show at On the Boards. Like so many performing arts groups, Whim W’Him pivoted to digital presentations during the pandemic, and I watched those. Although the company returned to live shows last season, I only attended one in person, so this season opener gave me a chance to renew my admiration for Whim W'Him's very fine dancers.

I

was so happy to see two veteran company members, Karl Watson and Jane

Cracovener, back on stage, along with five other talented dancers. But, to borrow a phrase

from the publication Seattle Dances, I have a brand-new dance crush on Andrew

McShea.

|

| Andy McShea photo @ Allina Yang |

I’d seen McShea perform before the pandemic shutdowns, and I watched him in Whim W'Him's streamed offerings. But I can trace the start of my new crush to August 10th, when WW was part of an evening of wonderful dance presented free at the renovated Volunteer Park Amphitheater.

That evening McShea performed a solo Wevers had choreographed for him. You know those social media posts, the ones with little arrows drawn on a photo to grab our attention? Watching McShea dance, I felt as if somebody had highlighted his body in flashing lights: Look at this dancer, Marcie!

I’m pretty sure it was the first thing I told friends about

that evening.

Anyways, back to the Erickson Theatre, where Whim W’Him’s Fall

2022 program opened on September 9th.

As I mentioned, it was wonderful to see Watson and

Cracovener. Nell Josephine and Michael Arellano are back this season, and

equally adept. I was also struck by new company members Leah Misano and Kyle

Sangil (who we actually got to see last May when Josephine was stricken with

appendicitis). Everyone was great. But I couldn’t take my eyes off McShea.

To be fair, in the first dance, created by Nicole von Arx,

the dancers’ heads were covered in black balaclavas for much of the time, so I

wasn’t always sure who I was watching. Believe me, I did spend some time trying to figure out who was who. But in Dolly Sfeir’s hard time for dreamers, the final work

of the evening, the masks were off, the dancers were distinctly visible and McShea just mesmerized me.

|

| Michael Arellano, left, Jane Cracovener and Andy McShea photo @ Allina Yang |

hard time for dreamers, theatrical and slightly absurd in a Pina Bausch-esque way, is set on and among a collection of early 20th century furniture, with costumes reminiscent of that same era. The three women wear brightly colored dresses with puffed cap sleeves and waist sashes, designed by Pacific Northwest Ballet’s Mark Zappone. For the men, Zappone created suits and vests cut from wide patterned plaid fabrics, paired with a variety of hats, from straw boaters to bowlers.

Sfeir, who is also a filmmaker,

gives each dancer a character to inhabit. Josephine was a sort of haughty socialite; Sangil, a tough. McShea was a sort of bittersweet

clown.

I was gobsmacked by his ability to seemingly melt his bones. One moment he’d be upright; the next, his body had dissolved to the floor, his legs and arms heading in directions that defied anatomy.

|

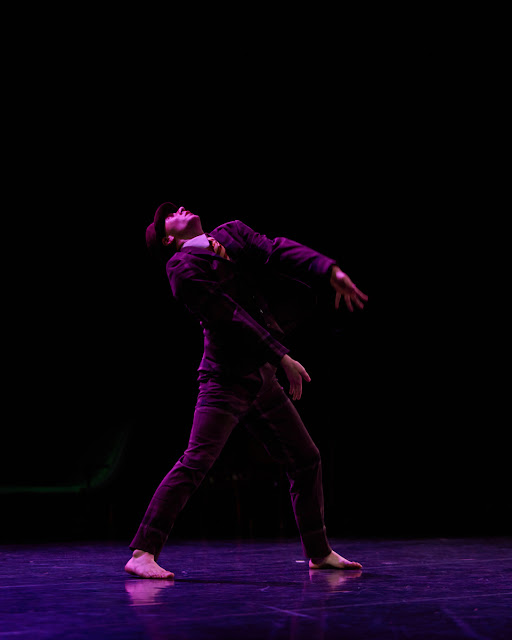

| Andy McShea, photo @ Jim Coleman |

McShea has sharp, high cheekbones, and an intensity in his eyes that contrast with his body’s fluidity. It was fascinating to watch how he paired those with the singular qualities of the other company members, qualities that transcend the dances they perform, like character traits that define us as individuals.

That's been one of my favorite things about watching Whim W’Him over

the years. We may never meet Wevers’ skilled dancers one one one, but we get to know them

because they bring their full selves--and their considerable technical and artistic gifts--to every work.

|

| Jim Kent, center, supported by Whim W'Him company members in Olivier Wevers' This is Not the Little Prince, photo courtesy Whim W'Him |

Dancers' performing lives are short, so we’re constantly meeting new artists at Whim W'Him and every other dance company. It's bittersweet indeed. The great Jim Kent left Whim W’Him last year after almost 12 seasons; Liane Aung departed last spring and both of them will be sorely missed.

.jpg) |

| Liane Aung, photo @ Bamberg Fine Arts |

But where wonderful artists leave, new talents step up to fill

the void. I look forward to getting to know the new company members, and to

stoke my dance crush on Andrew McShea.