|

| The inimitable Noelani Pantastico in Tea/Arabian in PNB's 2019 Nutcracker photo @ Angela Sterling |

A few weeks ago I jotted down some thoughts after the opening night of Pacific Northwest Ballet's latest production of George Balanchine's The Nutcracker. Mostly I was whining about rude audience members and their cellphones.

I posted my essay to social media, and was deluged with other stories about ridiculous behavior at live performances. But one commenter pulled me up short. She wondered what I thought about the ballet itself. And I realized that, while I'm impressed by the orchestra, the sets and costumes, and the big Snowflake and Flower waltzes, I don't go to Nutcracker to be awed by the show, not for the little girls twirling in party dresses onstage (and off), not even for the ballet itself.

|

| PNB principal dancer Leta Biasucci soared as Sugar Plum Fairy in 2019 photo @ Angela Sterling |

I go to see the dancers.

Before you respond 'well, duh Marcie,' let me explain.

I've seen this particular Nutcracker production at least 15 times since PNB debuted it in 2015; twice a year, sometimes three times, for seven seasons. The story is almost incidental to my experience. It's not that I dislike attending another performance; quite the opposite. I'm looking for dancers who shine.

|

| A Covid-era Clara and party guests, 2021. Ezra Thomson delights as Drosselmeier photo @ Angela Sterling |

During Act I I'm watching the kids in the party scene, particularly the various incarnations of Clara's naughty younger brother Fritz. I recognized him as one of last year's party boys. He has a wild head of hair and the military party hat wouldn't stay put. This year his Fritz was as exuberant as his hair.

Act II is all about featured company members, and for me, that's what makes Nutcracker a magical experience. Hefty roles like Sugar Plum Fairy and Dewdrop are pretty but also technically tricky, and I'm looking to see how the dancers navigate them.

|

| Here's principal dancer Elizabeth Murphy's 2017 Dewdrop. She's exponentially more lovely in 2022 photo @ Angela Sterling |

This year both Dewdrops I saw--principal dancers Angelica Generosa and Elizabeth Murphy--brought a deft and sparkling lightness to the role. And I was fascinated to watch soloists Sarah-Gabrielle Ryan and Ezra Thomson as Sugar Plum and her Cavalier. They had an almost tender partnership, with lots of eye contact. As always, Ryan threw her entire being into the role, and Thomson was her steady rock.

Beyond the usual suspects, it's always inspiring when a corps de ballet member gets a turn in the spotlight. PNB presents almost 40 shows this year, so there are many opportunities for less experienced company members to step up, whether to entertain an audience, or demonstrate to boss Peter Boal they have what it takes to go far.

|

| I haven't seen principal dancer James Yoichi Moore as the lead Candy Cane in several years. Angela Sterling captured this photo in 2017 |

It could be a chance at Sugar Plum, or the sinuous Tea/Arabian solo, and I'm always interested to see which tall dancer will climb stilts and don the 60-pound Mother Ginger dress, or dazzle us with double and triple hoop jumps as the lead Candy Cane.

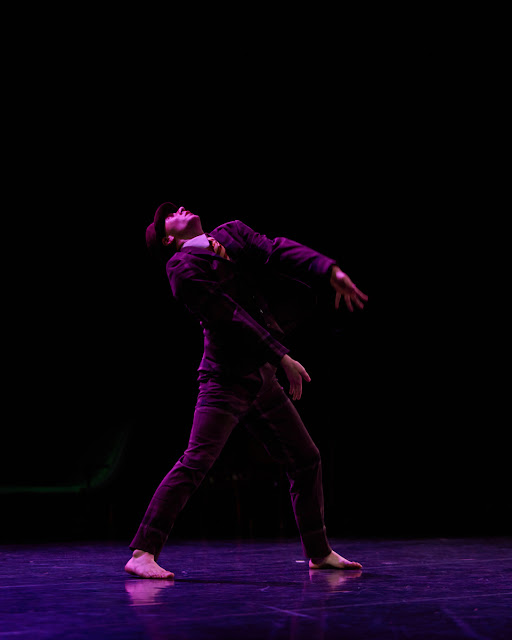

|

| Speaking of a dancer on fire--here's Corps member Kuu Sakuragi, definitely a dancer to watch. photo @ Angela Sterling |

I've seen two Nutcrackers this season, and in both, corps member Mark Cuddihee had his turn with the hoop. He mastered it the second time, shooting off a couple of double jumps in the big finale.

|

| That's Destiny Wimpye, front row on the left. Look at her pretty foot! photo @ Angela Sterling |

New apprentice Destiny Wimpye made her mark onstage, whether as one of several dozen Snowflakes, or radiating joy as a Marzipan shepherdess.

And this year I was dazzled by Zsilas Michael Hughes' Toy Soldier and Coffee/Spanish lead. Hughes literally kicked up their heels with abandon and it was so fun to watch.

I know that emerging star Ashton Edwards will be dancing Dewdrop on Thursday, December 22 alongside soloist Amanda Morgan as the Sugar Plum Fairy. I'm almost tempted to catch a third performance just to watch them both. You can get a ticket here.

Several years ago PNB Executive Director Ellen Walker talked to me about dancers who reflect light back to the audience, the dancers we watch onstage then thumb through our program to identify. I've never forgotten her words.

Unlike so many (most) dance writers, I don't come to this obsession from a dance background. I love to watch great performances, but more than technical prowess, I'm interested in that slippery, indefinable je ne sais quoi that imbues an artist with something that sets them apart from the crowd. In Spanish the word is 'duende.' It's about soul, and a passion that infuses each performance, whether the first or the 40th Nutcracker in this case.

|

| I *think* this is soloist Christopher D'Ariano at Mother Ginger. This photo by @ Angela Sterling was taken in 2019, but D'Ariano stole the show again this year. |

After the holiday decorations, the costumes and sets get stowed away until next season, I'll be thinking of those dancers whose souls burn with that interior fire, that duende. And I'm so grateful to know I'll get to watch them again--and again--on the McCaw Hall stage.

.jpg)